Re-framing the Black Woman Through the Lens and Pen of Pan-African Female Filmmakers

by Alethea Russell, WIFP

July, 2013

I have seen them in magazines, read about them in novels, watched them on movie and television screens but have yet to meet women like Aunt Jemima, Mammy, Jezebel or Sapphire face-to-face; that’s not to say they don’t exist in real-life embodiments. Appearing in both print and electronic forms throughout the century, these caricatures have been over-presented to audiences as representative of black women in the United States–images that suggest we are subservient, over-sexualized, angry, and malicious beings. In 2013, modern media hasn’t deviated much from early depictions of African American females. One major difference is how black people, women especially, play a role in perpetuating these non-sensical embellishments.

Art—as proposed by Aristotle in Poetics—which has since then expanded to many facets, is supposed to be true to life. The human condition so tightly folded into pieces of literature; pulsating through speakers; etched and colored on concrete and linen. But no art form is as versatile and powerful as film. It encompasses a multitude of mediums—photography, performing arts, animation, writing, and music, just to name a handful. According to a Russian filmmaker, it is distinctively the most realistic of all the arts. Though it draws influence from things like literature and theater, it’s profitability, dynamic quality, and resonance is unparalleled.

The United States movie industry alone brings in upward of $100 billion a year. Our entertainment, language, and policies dominate global industries—meaning American culture and attitudes infiltrate international consciousness. Therefore, the repetitious and shallow portrayal of certain social groups are met with acceptance by both domestic and foreign consumers as true to life. So if life imitates art and art imitates life then what does the content being produced by Hollywood and the influx of art house films created by Black African-oriented creators say about our society? Considering 90 percent of the world’s media is a product of six major corporations—from newspaper, magazine, and book publications, radio and television broadcasts, the movie and music industries, video game development, and cell phone and internet service—it’s no wonder why the mainstream sounds and images we consume daily are monotonous—boasting boasting in stereotypes, misogyny, and vanity—pursuant of the capitalistic and colonialistic ideals of its creators, covertly preying on the proletariat. A comedian once said Hollywood lets audiences know exactly how it feels about women and Black people. The way it’s done is through selective inclusion and other modes of abuse of power, whether intentional or not. What is being said, as aforementioned, is the reinforcement of ethnic and gender bias: women are merely objects subjected to voyeurism and possession; racial minorities are exotic/otherworldly or completely invisible.

No one knows the weight of both existences better than black women. “Most important is the role of the cinema in the construction of peoples’ consciousness,” Mauritanian filmmaker and actor Med Hondo declares. “Cinema is the mechanism par excellence for penetrating the minds of our peoples, influencing their everyday social behavior, directing them, diverting them from their historic national responsibilities.” These characteristics distinguish it from the members of its creative family. The words and pictures in our mind, cohesive and deliberate, form association. It is the same type of programming used on toddlers to teach them how to say their ABCs and spell. Only we’re not dealing with fruit and colors. We’re dealing with people and how we perceive each other.

Fortunately, there’s hope. Women and racial minorites are emerging in numbers to challenge the status quo and write from their point-of-view, a perspective deficient in mainstream literature, journalism, and scriptwriting and so often dictated by privileged, middle-aged, Euro-minded men. It is the stubbornness and lack of forward-thinking and not, in fact, the consensus of the public that deems black cinema unmarketable and undesirable. “Pariah,” a short-film-turned-full-length-drama about a high school aged teenager learning to love herself directed by Dee Rees was turned down by many film execs who the creator claims used coded language to dismiss the story because it was “too black” and “too gay.” Since its release it has won 25 awards, including the GLAAD Outstanding Film Award last year, and received over three dozen film festivals acceptances. This response has led Rees to believe “audiences are progressive” and “want to see different kinds of stories.” Unfortunately, Hollywood isn’t supportive of these types of projects. And with competition from television and on-demand services, the film industry is slowly losing its appeal.

For a decade Ava DuVernay worked as a movie and television publicist, representing some of Hollywood’s top directors, including Clint Eastwood and Michael Mann, before taking the leap into film-making. She even owned her own firm called DVA Media & Marketing. Her hard work behind industry greats prepared her to take more control. In 2011, she developed AFFRM, the African American Film Festival Releasing Movement which distributes Afro-centric art films and is responsible for the release of her debut narrative “I Will Follow.” Produced solely out of her own pocket, “I Will Follow,” a self reflexive story, spends twenty-four hours with a woman (played by Salli Richardson-Whitfield) who has to pack up her beloved aunt’s (played by Beverly Todd) belongings following the cancer-stricken relative’s death. Though comprised of a black cast, the story is universal.

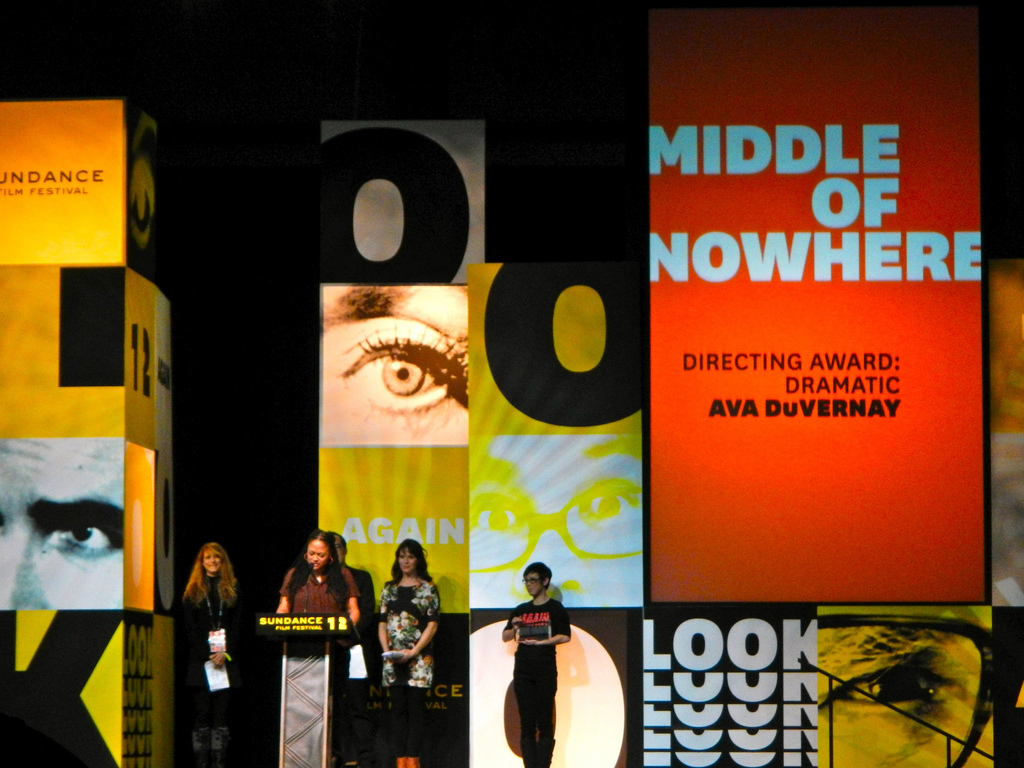

The success of her introductory film correlates to Ree’s sentiments that there is an audience for black cinema and that, according to DuVernay, films of color don’t have to be the typical action, comedy, or historical account to get movie lovers’ attention. Less than a year later came her sophomore effort, “Middle of Nowhere,” which was distributed with the help of Participant Media and endorsed via Twitter by media mogul Oprah Winfrey. Again, boasting with a black cast and, more importantly, a black female lead (Emayatzy Corinealdi). It opened to an impressive $78,000 on only six screens. By the next week, it expanded to three times as many theaters. While she may not have made a profit from multiplex screenings, the entrepreneur and artist is well on her way to developing an imitable model for producing quality indie films. She values the work of volunteers, social media, and cultivating relationships with other like-minded creatives in addition to traditional PR tactics which have allowed her to produce, promote, and distribute her films without interference from a major studio. She has chosen this path as a way to ensure indie black films continue to be made and are given the platform to be displayed.

Just recently ESPN aired “Venus Vs,” a short documentary directed by DuVernay and highlighting Venus Williams’ dedication to continue trailblazing athlete Billie Jean King’s pay equity campaign for winning grand slam women players. This comes just months after the filmmaker won Sundance’s 2012 Best Director Award, the first for an African American female. She was actually approached by the sports network to develop a documentary on a subject of her own choosing for their Nine at IX series celebrating the 40th anniversary of Title IX, the legislation that forbids any federally funded academic program or activity from exercising gender discriminating. Having grown up in the same neighborhood as the enterprising tennis star, DuVernay felt compelled to share this much overlooked story. In the style of her previous work she revolves the narrative around the POV of a Black woman. We are given a glimpse into Williams’ character. Not as an afterthought or a victim. Non-stereotypical. Multidimensional. Heroic. Human.

Already working on another feature film, DuVernay has just been announced as Lee Daniels’ replacement as director of the biopic “Selma” about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s voting rights advocacy. As if that’s not enough for the 40-year old who changed career paths later in life, this year she became the second black woman invited to join the Academy Awards’ director branch. Kasi Lemmons preceded her in 2012. This means more people in places of influence able to act a voice for women of color.

It seems as though life these days is moving fast for the South Central L.A. native. “It’s a great time to be a black female, or female filmmaker,” she boasts. “This is the time where we can pick up our cameras and make the films we want to make.” She walks in essence of visionaries like Tressie Souders, claimed to be the first black woman to direct a film in the United States (“A Woman’s Error,” 1922); Ayoka Chenzira, the Spelman College professor noted as the first African American woman animator (“Hairpiece: A Film for Nappy Headed People,” 1985); Joy Shannon, the first African American woman filmmaker to receive a home video release (“Uptown Angel,” 1989); Julie Dash, the first African American woman to have her film distributed nationally (“Daughters of the Dust,” 1991); Leslie Harris, the first black woman to have her film distributed by a major theatrical distributor (“Just Another Girl on the I.R.T.,” 1993); Audrey Lewis, the first African American woman to write and direct a sci-fi feature (“The Gifted,” 1993); Darnell Martin, the first African American woman to direct a feature film produced by a major studio (“I Like It Like That,” 1994); Dianne Houston, first and only black woman nominated for an Academy Award for a short film (“Tuesday Morning Ride,” 1995); Cheryl Dunye, writer, director, and star of the first African American lesbian feature film (“The Watermelon Woman,” 1996); Kasi Lemmons, creator of the highest-grossing independent film of 1997 (“Eve’s Bayou”); Gina Prince-Bythewood, writer and director of the highest-grossing film by an African American woman (“Love & Basketball,” 2000); Aishah Shahidah Simmons, rape and incest survivor, activist, LGBT Studies lecturer and documentary filmmaker (No! The Rape Documentary,” 2006); Maureen Aladin, Jessica Hartley & Ella Turenne, founders of SistaPac Productions and creators of “Kindred,” a web series that follows three African American women dealing with life issues such as sexual harassment, cheating, substance abuse, fatal diseases, racism, and homosexuality; Issa Rae, a writer, director, producer, and TV show hostess whose popular web series “Misadventures of Awkward Black Girl” is one of a few monetizing through YouTube; and Mara Brock Akil, creator of the number one scripted show on cable, “The Game,” and BET’s first original drama “Being Mary Jane,” which debuted to record numbers—making it the year’s top weeknight movie premiere for the 18-49 demographic thus far.

Of course, black as a social identifier is not synonymous with African American. Women of color internationally make movies and are shaping their own images on- and off-screen, too. It is said that African cinema is genuinely feminist, affirming the woman’s value in modern African societies, but generally men have been awarded the coveted role of director. Yet pressing the image of women through the lens of the male gaze. Is it encouraging to know that diasporic women, especially black Africans like the ones I shall list, have sprouted as celebrated storytellers in Third Cinema and guerrilla filmmaking. Illustrators of black woman subjectivity include Tsitsi Dangarembga, writer of Zimbabwe’s highest-grossing film and the first black Zimbabwean woman to director a feature film (“Neria,” 1993; “Everyone’s Child,” 1996). She is also an acclaimed novelist; Euzhan Palcy, from Mozambique, is the first woman of African descent to direct a major feature film (“Dry White Season,” 1989); Dash Harris, a black Panamanian whose documentary “Negro” explores Afro-Latino identity (2012); Rahel Zegeye, responsible for “Beirut,” a documentary inspired by her frightening experience as an Ethiopian migrant and domestic worker in the Middle Eastern city (2006); Mira Nair, where the theme of Indian and multicultural identity is found throughout the Indian filmmaker’s movies (“Mississippi Masala,” 1991; “The Perez Family,” 1995; and “The Namesake,” 2006); and Pratibha Parmar, the Kenyan-born Indian who has dedicated her career to community outreach and using cinema as a tool for educating audiences about topics like lesbianism and female genital mutilation (“Warrior Marks,” 1993 and “Nina’s Heavenly Delights,” 2006).

At a glance we may look like the Aunt Jemima, Baby Mama, Hoochie Mama, Welfare Recipient, Video Vixen, Side Chick, Angry Black Female, or Token Black Bestie you saw on the screen, but our story is deeper than the surface. We come from a long line of griottes, nurturers, rulers, and keepers of culture. It’s in our nature to be seen and heard. Though there is always someone to fit the stereotype, people change. Nonetheless, black women have the right to be who they want to be and deserve to be represented properly. A major part of film or art in any form is self-expression. It’s important that media be free, diverse, and ever-evolving. Democracy gives voice to the stories, beliefs, and overall existence of its constituents. Most, if not all, of these luminous talents have criticized how disheartening it is to go to a movie or turn on the TV and not see a reflection of themselves. Why are constantly measured by the white gaze? Where are the black women authors? Who better to write about or portray a woman of color other than a woman of color? If we are shown only a fragment of our societies as told by Hollywood then they ignore the other individuals who comprise and push forward these communities. For the same reason silent film began including sound and black & whites blossomed into color, these objects–sound and color–are true to life as is the case with black women. They exist in variations of beauty and until we view them as necessary components to understanding language, culture, history and humanity then the story still goes untold. Dianne Houston states, “Black women historically have been presented as either subhuman or superhuman. Now we are starting to emerge as simply human, and that’s a wonderful thing.” As a student of film and daydreamer I say thanks to all the fearless lens holders and storytellers, unsung or otherwise. I shall make no more excuses to keep me from shaping my own world, declaring my existence, one frame at a time.

Bibliography

“Africa: Women Filmmakers Tell Their Stories.” All Africa. All Africa Global Media. 17, Feb 2012. Web. http://allafrica.com/stories/201202171378.html

“Behind the Lens: The Black Women of Film.” Separate Cinema. 2008. Web.

http://www.separatecinema.com/exhibits_behindthelens.html

Carmichael, Emma. “’I Have Stories I Want to Tell’: A Conversation with Filmmaker Ava DuVernay.” The Hairpin. 2, July 2013. Web. http://thehairpin.com/2013/07/i-have-stories-i-want-to-tell-a-conversation-with-filmmaker-ava-duvernay

Dovey, Lindiwe. “New Looks: The Rise of African Women Filmmakers.” Feminist Africa. African Gender Institute: University of Cape Town. (2002). no. 16. 16-36.

Hope, Ted. “Guest Post: Ava DuVernay ‘What Color is Indie.’ Indie Wire. 4, May 2011. Web.

http://blogs.indiewire.com/tedhope/guest_post_ava_duvernay_what_color_is_indie

Makarechi, Kia. “Dee Rees’ ‘Pariah’ and Hollywood’s Inability to Include Black Black Americans.”

HuffPost Arts & Culture. Huffington Post. 9, Jan 2012. Web. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/01/06/dee-rees-pariah-hollywood-race-problem-black-

actors_n_1190478.html

McLeod, Corinne. “Teaching Aberrance: Cinema as a Site for African Feminism.” Journal of International Women’s Studies, 12 no. 4. (July 2011). 79-92.

Tarkovsky, Andrey. “The Beginning.” Sculpting in Time: Reflections of the Cinema. Eighth University of Texas Press: Austin, TX. 2003. Print.

Welton, Yvonne. “Feature Films Directed by African American Women.” Sisters in Cinema. Our Film Works. Web.http://www.sistersincinema.com/joomla/index.phpoption=com_content&task= view&id=70&Itemid=97

Women Make Movies. 2013. Web. http://www.wmm.com

The Women’s Institute for Freedom of the Press

The Women’s Institute for Freedom of the Press